Watercolors are an oft-misunderstood medium with a bad reputation for longevity and importance in the fine art world. But, those ideas are anything but true. We’ve spoken with artists and consultants to explain some of these misperceptions and to ease the mind of new or seasoned collectors considering adding watercolor to their collection.

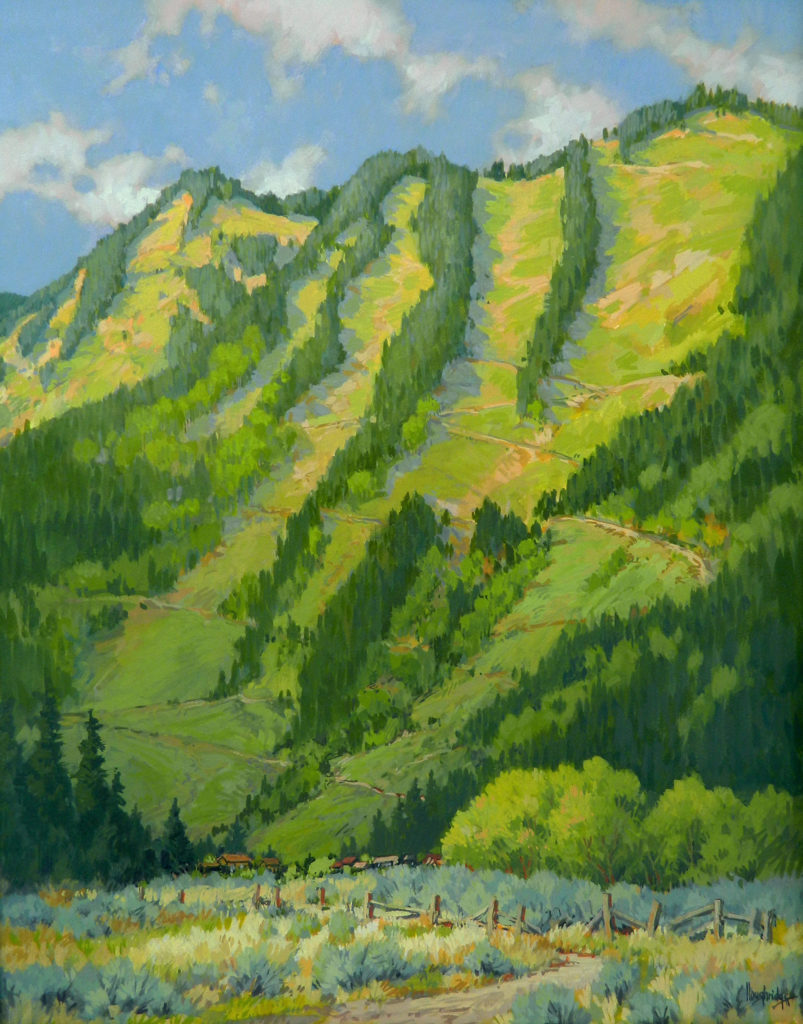

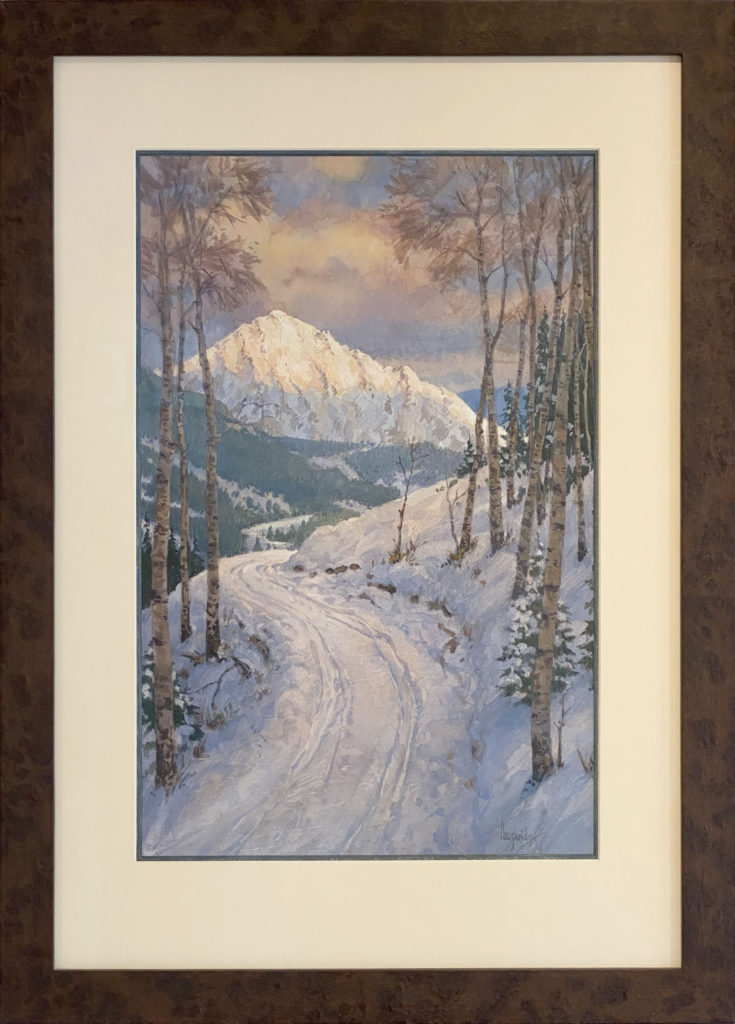

Watercolor paintings are a great access point for collectors who are drawn to an artist but are not yet ready to commit to a larger painting. Many artists have a medium of preference when creating studies for larger paintings, and watercolor is a favorite for such plein air sketches and more detailed studies. For example, Leon Loughridge, a woodblock printmaker, finds his primary medium of woodblock printmaking to be a continuation of his watercolor sketches done in plein air and detailed watercolor paintings created in the studio.

Works on paper have great value for collectors. Typically more affordable than an oil painting, watercolors are a perfect entry point for new collectors. While watercolor has the perception of a low-level access point for painters, watercolor is an unforgiving medium that speaks to an artist’s proficiency. Thanks to the advancements of pigments, much richer, non-fading colors are possible, further shifting watercolor from a quick-reference to fine art.

Watercolor sometimes has an outdated reputation for being susceptible to time and elements, historically hindering its acceptance in some circles as “fine art.” Technology and time have greatly improved the medium: richer, more stable pigments are in use; finer, more uniform paper has been developed; and processes to preserve the work are common place, such as use of varnishes, mattes, and museum-quality UV resistant glass. Watercolors can be expected to last many, many generations.

Before a watercolor is installed, many processes are taken to ensure the longevity of the work. Artists will spray a watercolor with an aerosol varnish that keeps the pigment fresh. The matte will likely be a nonacidic matte to lay between the watercolor and the glass. And the glass is likely to be museum quality (UV deflecting) glass – bonus points for the much more expensive non-glare option.

“With my wife Wendy’s help, I like to frame watercolor works in the same way that etchings are treated,” Ostlind explains. “The difference between prints and paintings becomes blurred when I create watercolor prints.

“Most works on paper are best protected with matting that places a safe space between the art surface and a light filtering sheet of glass. I do not varnish nor seal works on paper with a spray finish. In order to have an archival presentation it is nice to use a reputable 100% rag paper, 100% rag archival museum quality matting, and top it off with UV filtering glass.”

“The etching inks I use are carbon based and that means lightfast. To tint a print or do a watercolor painting the important thing is to check the lightfast rating of the pigments. It seems that most of the old colors that could fade over time have been replaced with matching permanent hues. Some of the new vibrant watercolor paints are less lightfast than most of the old workhorse colors and I avoid them.

“So, it all gets down to doing the best to present and preserve works on paper in a way that will keep them looking good into the unforeseeable future. I guess it always gets down to the idea that life is short and art is long. But, I don’t like the idea that life is short.”

Like most art, watercolor paintings should be installed in an area that does not receive prolonged direct sunlight to preserve the color. Works on paper can also be susceptible to changes in humidity or intense humidity, but this problem is much less common with home climate control like HVAC systems.

Watercolor is by no means a new medium to the fine art world, and has its own great history. Historically, watercolors have been used as a form of study or observation, with naturalist use of watercolor going back to John James Audubon (1785-1851) who attempted to paint a pictorial record of the bird species of North America, impressing with the precision that comes from close observation and fine handling of the medium, a practice still used by naturalists such as our own naturalist and printmaker Sherrie York.

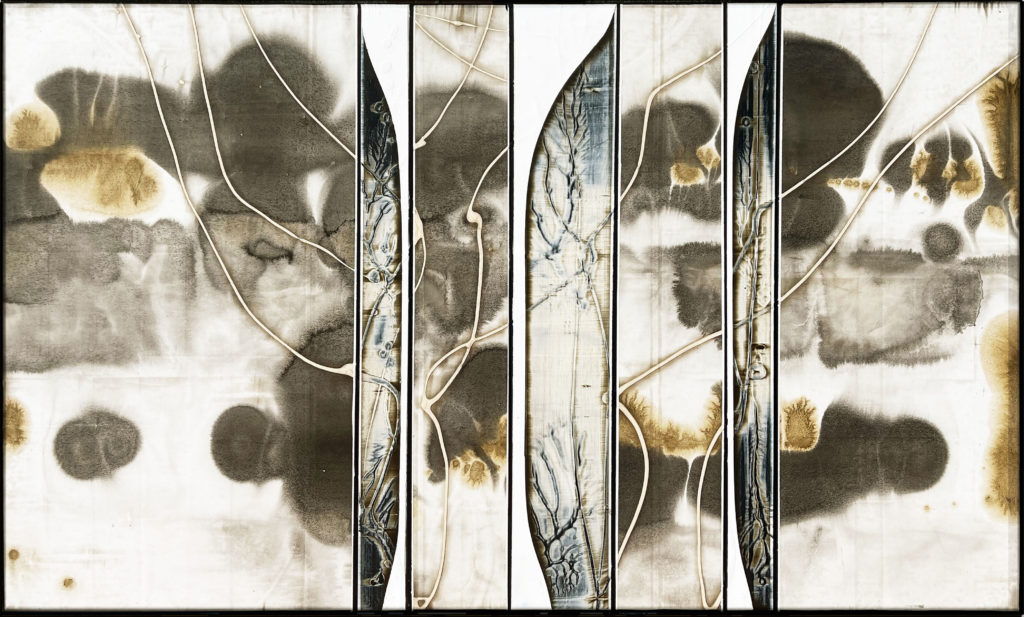

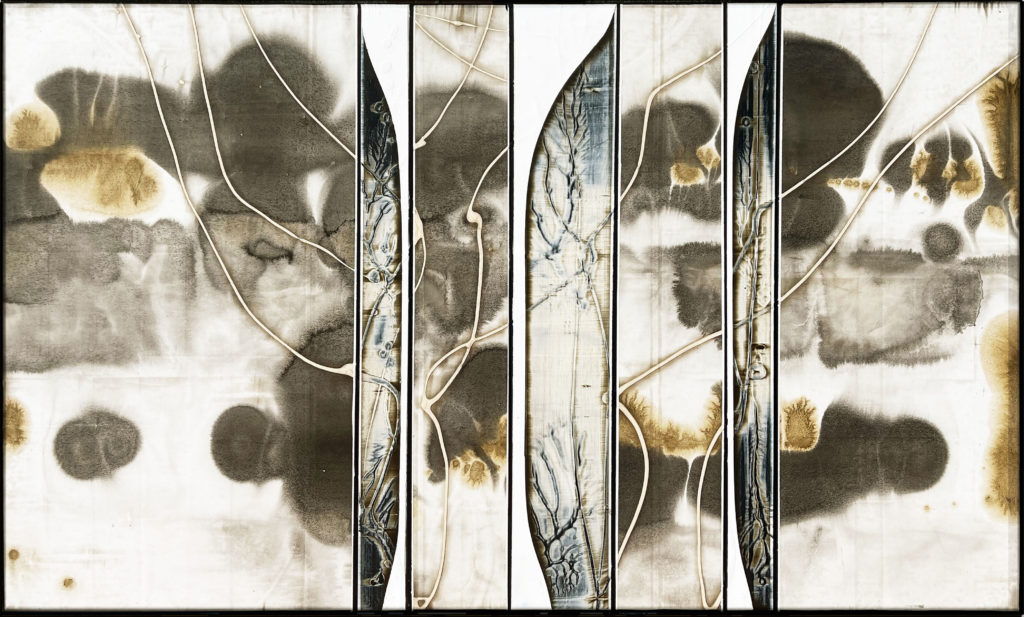

Watercolor has leapt forward as a means of expression and documentation, from the cavemen to the Renaissance, to Britain’s J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Ruskin (1819-1900) who helped elevate watercolor as fine art, to Vincent Van Gough (1853-1890) who painted over 150 watercolors in his lifetime, to the mid-19th century American Hudson River School which influenced and included preeminent figures in American art such as Winslow Homer (1836-1910), John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), and Edward Hopper (1882-1967), to American graphic designer Paul Rand (1914-1996). Take a look at the use of watercolors by mixed media artist Michael Kessler, printmakers Joel Ostlind and Sherrie York, and woodblock printmaker and watercolor artist, Leon Loughridge, and explore works on paper here.