Michael Wisner grew up in an artistic household in Maryland. His father, Tom Wisner, was known as the “Bard of the Chesapeake,” a musician, songwriter, poet, artist, and educator whose work has found a permanent home in Smithsonian Folkways. With this exposure throughout his childhood and adult life, Michael always knew that being an artist was inherently part of who he is, but the struggles he witnessed in his father’s career sent him on a detour in the opposite direction to work in cancer research and pharmaceuticals in his early 20s. However, his artistic call was ultimately so strong that it led him right to California to study at the ISOMATA School in Idyllwild where he could learn ceramics in the Southwest traditional from Native American artists. There Michael discovered the work of Juan Quezada, “the patriarch of pottery tradition in Mexico,” according to Michael.

Quezada was born in a poor rural town in Chihuahua. As a boy, he discovered shards of pre-Hispanic pottery of the Mimbres and Casas Grandes cultures and realized all the resources to make these ceramics must be naturally available, so he started to investigate how to make clay from the land. And he did, making remarkable improvements to the technologies passed on from one generation to another. Eventually, his town became a village housing over 400 exceptional ceramic artists, and Michael Wisner became his #1 student.

In 1989, Michael journeyed down to Mata Ortiz, a small mountain town three hours south of the US-Mexican border, and arrived at the doorstep of Quezada’s home, where he told the artist how much he admired his work and wished to learn from him. Michael was immediately welcomed into the Quezada family, and thus began an 18-year mentorship and lifelong friendship with the artist. During this time, Wisner learned to create clay from the land and paint pots in the traditional technique, while finding his own style. “That’s the model—not to copy anything but to riff off it, to collaborate and keep moving,” reflects Wisner. During this time, he often asked himself, “what do I love about these native traditions, techniques, and technology, and what can I do to bring my own personal voice in that speaks from my contemporary culture?”

It was an artist residency at Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass, Colorado that provided the perfect landing place for Michael to explore his own style, while being exposed to new cultures and techniques. He knew that the painted pots he was creating at that time put him in the corner of Southwestern Art to those unwilling to open their minds to the contemporary expressions that Michael saw, so he pulled away from the style after 15 years.

Somewhere after his journey to California, Michael moved to Aspen. He was enthralled by the natural landscapes and the surrounding beauty, as well as the funky-artsy community that thrived in those times, when artists could afford to live downtown and shape the culture appropriately. “When humans are happy and feel fulfilled, art just pours out of us,” reflects Wisner. “Some people create art out of struggle and distress, but that’s not for me. It’s created best when I am happy and there is a resonance in my life.” Happy he was—teaching skiing in the Winter, travelling to Mexico in the Spring and Fall to study with Quezada, exploring the wilderness, discovering his style.

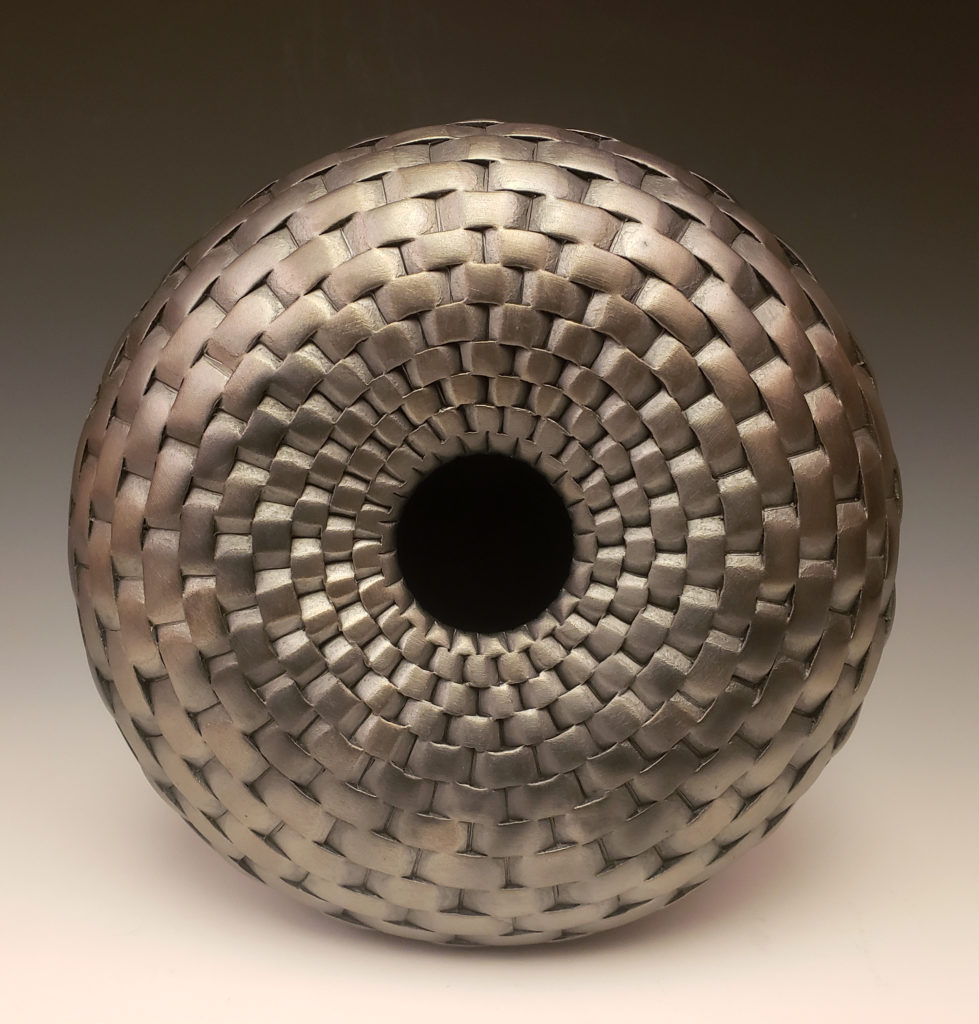

He allowed his process to take more time, rather than money. He found satisfaction in finding a deposit of clay in the ditch along Owl Creek Road, cleaning it, shaping it, and firing it into a fine art piece. He allowed his spirit to draw him towards small moments on hikes—stopping to study the sacred geometry of a pinecone, weavings, seed pods or a wandering river—and taking that curiosity back to his studio in Woody Creek to recreate three-dimensional patterns in clay with tools he would make himself.

Wisner’s pots are all hand-coiled in a technique he learned from Quezada, and carved into patterns that are inspired by nature. He is drawn to repeated geometry, the sacred geometry that is visible throughout nature. Fibonacci and other intelligent patterns are done over and over again in nature. “It’s not for a random reason. Those patterns make sense structurally, and on a spiritual level as well. They are woven into us,” reflects Wisner. “People respond to this work, as it is something inside all of us.”

“Sacred geometry is a natural order of the cosmos, these repeating patterns. I don’t make these things up, they come out of me. They started happening after I started doing 3-month meditation retreats. My spiritual experience is we have a lot of things reversed—we look from the outside like we are people trying to invent them, but we are uncovering them.” Looking at Wisner’s patterns meticulously carved into clay, it would seem mathematics and careful measurements must be involved, and they were, early on in the process. He started with a mathematical approach, by dividing the opening of a pot into 1/64ths and measuring out his meticulous patterns. But to the artist, they were too perfect. “They looked plastic and lost their life,” he recalls. Wisner explained that it’s in our culture to make everything precise, but in Native American and African cultures, the intention to make rhythm and pattern is there, but they don’t make it spot on, so as not to lose its organic nature, and for the viewer to feel the handmade quality. True to form, he started creating his patterns free-hand and they came to life, with the understanding that, “if you find something that looks symmetrical in nature, if you really look at it, you’ll see it’s approximate. Perfect is a word a lot of people like to use, but that’s not it.”

Of these patterns in sacred geometry, Wisner, an English, Spanish, and Portuguese speaker, thinks of it as a language. “I am learning a language and then figuring out how to use it. To translate into clay the way nature has found to lay down shingles—one on top of another—and once I’ve decoded the intelligence of it, it’s like a jazz musician riffing.” Wisner doesn’t tire of his work because he is constantly evolving and exploring his relationship to clay and form. He enjoys the repeating form and cadence of it, elongating a pattern, shrinking it, trimming the corners. “That’s the fun in the studio — creating 15 permeations of the original idea, then collaboration continues as I lay it down on different shapes.”

Michael Wisner’s work can be viewed at Ann Korologos Gallery in Basalt, Colorado, as well as on www.korologosgallery.com. A lucky few are invited to visit his studio in the Summer months, when the artist is available.